The Scopes ‘Monkey’ Trial of 1925

University of Kassel, WS 2003/2004

Class: Topics in US-History II, Dr. T. Clark

Presentation by Andrea Sternberg-Holfeld

January 12th, 2004

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Background

2. 1 Science-historical Background

2.2 Socio-political Background

3. The Trial

3.1 The Tennessee Evolution Law

3.2 The Antagonists

3.2.1 Clarence Seward Darrow (1857-1938)

3.2.2 William Jennings Bryan (1860-1925)

3.3 Chronology of Events

3.4 The Public

3.5 The Press

3.6 The Biology Book

3.7 Hell and the High Schools

4. Scopes today

4.1 How the Scopes Trial is percieved today

4.2 Anti-evolution Activities

5. Conclusion

Sources

***********************************************************************

1. Introduction

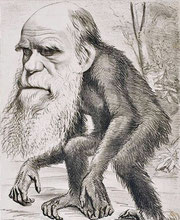

In the early 20th century, there was a considerable rise in religious Fundamentalism in the United States. The name Fundamentalism was derived from a series of pamphlets, The Fundamentals, published first in 1910 (Cayton & Williams, 2001). One main target of fundamentalist attack was Charles Darwin’s theory of organic evolution. Fundamentalists believed in the inerrancy and absolute truth of the Scripture, and therefore they considered Darwin’s theory subversive and dangerous since it obviously contradicted Creation as described in the Bible. Inspired by those Fundamentalists, Legislators in 20 states introduced bills to prohibit the teaching of evolution in publicly funded schools in 1921-1922, and several states enacted such laws in the 1920ies (Boyer, 2002). In Tennessee, it was the Butler law that was adopted in March 1925. In order to challenge the constitutionality of the Tennessee anti-evolution law, the American Civil Liberties Union staged a trial against the biology teacher Scopes who was accused of having taught evolution in a public school and thus violated the law. The so-called Scopes "Monkey" Trial, that took place in the small town of Dayton in July 1925, aroused a lot of public interest, even abroad, and was the first one broadcast on radio. This was partly due to the confrontation between two of the greatest legal minds of the time, Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan, as well as to the articles by the infamous journalist H.L. Mencken. Though Scopes was found guilty, the trial was a defeat for religious Fundamentalism and its representants.

***********************************************************************

2. Background

2.1 Science-historical Background

As the absolute authority of the Church declined in 18-century Europe (Age of Enlightenment), scientists did not rely solely on the Bible and Aristotle as the source of all answers to all the questions anymore, but started to observe nature in order to understand it. They discovered natural laws to explain observations of natural systems, demonstrated that many types of plants and animals had become extinct, and that fossils differed through time. They became convinced that species were not immutable, but changed over time. While special creation of each species was the prevalent belief even among scientists in the first half of the 19th century, the idea of evolution became increasingly acceptable as more and more evidence for evolution was uncovered. But it was still lacking an overall theoretical framework to explain its mechanisms. This theoretical framework was finally provided by Charles Robert Darwin (1809-1882) with the publication of his famous book "The Origin of Species" in 1859 (Wicander & Monroe, 1989)

Darwin’s career as a naturalist started with his 5-year voyage on the H.M.S. Beagle in October 1831. He had just recently graduated in theology from Christ’s College and, at that time, fully accepted the biblical account of creation as historical fact. But in the course of the voyage this should change. Based on the observations he made on this trip, especially of the flora and fauna of the Galapagos and Cape Verde Islands, the fossil record, and the practice of artificial selection in plant and animal breeding, he developed his theory of organic evolution which stated that species are not fixed but are descendants of life-forms that existed in the past. The changes, respectively, were due to the mechanism of natural selection, a random process in which accidental variations enabled new species to emerge and triumph over competitors. Most naturalists accepted Darwin’s theory almost immediately. Nevertheless, they did not abandon the Judeo-Christian tradition, but accepted Genesis as a symbolic account, not a factual account of creation. In America, though, most naturalists were, because of their religious commitments, more reluctant and began to see natural selection as a promising hypothesis only during the 1870ies (Wicander & Monroe, 1989, Cayton & Williams, 2001).

After the publication of Darwin’s book, a hot public controversy arose. To question divine creation in any way was considered an act of heresy by literalist theologians. Darwin’s theory challenged not only the believe in creation as described in the 1st book of Genesis with fixed species from the beginning but also the unique character of human beings as distinct from and far superior to all other species, created in the image of God. But there were also those who, like the Catholic theologian Francis P. Kenrick in his Theologia Dogmatica of 1858, explicitly warned not to interpret Scripture in ways that place it in opposition to the discoveries of science. They claimed that natural selection was fully compatible with Christian ideas of divine order and purpose. The catholic theologian John A. Zahm even said in his Evolution and Dogma of 1896 that evolution ennobles our conceptions of God. Ultimately, as in other conflicts between science and religion (e.g. in the trial of Galileo in 1633 for supporting the Copernican theory that the earth revolved around the sun, rather than - as the Bible suggests - the other way around) most churches and theologians eventually accepted the teaching of evolution. (Cayton & Williams, 2001, http://www.law.umkc.edu).

2.2 Socio-political Background

In the 1920ies, with a considerable rise in religious Fundamentalism, Darwin and religion came into regular conflict in the United States. There were several interrelated reasons for this phenomenon. The early 1920s found social patterns in chaos. Cultural turbulance, disorienting social changes, a postwar crisis of values, and hard times for American agriculture made those years an unusually stressful and conflictridden decade. The urban population outnumbering the rural in the census of 1920 for the first time, an increasing conflict between rural traditionalism and urban modernity ensued. For traditionalists, the ever-growing city was the center of new modes of modern life, including shifts in traditional gender roles, family life, leasure activities and morals, that rejected all rural tradition, and thus it was a source of increasing uneasiness and insecurity. Fundamentalism was one outlet of the anti-modern and retrospective impulses in early-twentieth-century American culture. World War I also played a role in the growing hostility against modernity. The war with its advanced technology, industrial processes, and bureaucratic control seemed to personify the worst horrors of modern society. A collective nostalgia swept the country for the relative simplicity and unity of prewar society in contrast to the multiplicity and uncertainty of the present, and, in rural areas, particularly in the South and Midwest, Americans turned to their faith for comfort and stability (Boyer, 2002, Cayton & Williams, 2001, Lindner, 2002, http://xroads.virginia.edu).

A theological reason for the increase in Fundamentalism was the rise of theological liberalism against which Fundamentalists and evangelical Christians protested. Modern theologians started to apply scientific concepts and research methods to theology like the application of critical methods in the study of sacred texts, and the comparative analysis of religious traditions, the so-called cultural approach. It emphasized the force of culture on the development of religion, and interpreted changing conceptions of God as reflections of changes in cultural circumstances, whereas higher criticism meant probing questions about authorship, audience, dating, and historical context for the texts that make up the Bible. Fundamentalists rejected those approaches since they seemed to question both the superiority of Christianity to other religions as the only true one and the authenticity of the Scripture, which they considered as being divinely inspired and without error in any details. The liberal idea that the historical Jesus was only a moral example, not a supernatural Savior born of a virgin, and that the biblical statement is only a symbol, not a historical fact, was fiercely attacked by the Fundamentalists. Developments like evolutionary theory, higher criticism, and comparative religion were considered signs of present-day corruption. The Fundamentalists saw themselves as defending Christian belief attacked by the liberals, and bitter denominational battles ensued in the wake of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy of the 1920ies (Cayton & Williams, 2001).

That teaching of evolution became a front-burner issue in the 1920s was also due to the fact that universal publicly funded high-school education was just becoming standard across the country then, placing the question of what the new high schools should teach very much on the minds of activists, newspaper editors, and politicians. Another factor was that the prestige of science had grown steadily, challenging religion’s cultural standing. Paleontologists, for example, were beginning to accumulate evidence that human beings descended from earlier primates. Scientific findings of ‘cave men’ were banner headline stories of the time, and though some turned out to be hoaxes, some were confirmed as genuine. This confirmed the assumption that humanity was not the centerpiece of nature and goal of evolution, but fully located in the realm of the natural, an assumption difficult to believe for many churchgoers. On this naturalistic basis, science became more and more interested in the biology of human life. Special attention was directed to instincts, drives, and heredity. One result of this approach was a flourishing eugenics movement and pseudo-scientifically supported racism (Boyer, 2002, Cayton & Williams, 2001, Easterbrook, n.d.). And Darwin himself did not shy away from eugenics.

"We civilized men," Darwin declared, "do our utmost to check the [natural] process of elimination [by natural selection]; we build asylums for the imbecile, the maimed, and the sick; we institute poor-laws; and our medical men exert their utmost skill to save the life of every one to the last moment. There is reason to believe that vaccination has preserved thousands, who from a weak constitution would formerly have succumbed to small-pox. Thus the weak members of civilized societies propagate their kind. No one who has attended to the breeding of domestic animals will doubt that this must be highly injurious to the race of man. It is surprising how soon a want of care, or care wrongly directed, leads to the degeneration of a domestic race; but excepting in the case of man himself, hardly any one is so ignorant as to allow his worst animals to breed." (in Wiker, 2002)

Combined with the then fashionable ‘Social Darwinism,’ which held that the mechanisms of natural selection, the ‘survival of the fittest,’ should be applied to human society, these dark sides of Darwinism discredited evolutionary theory in the eyes of many alarmed members of the clergy, and strengthened general opposition towards evolution (Easterbrook, n.d.). All those aspects explain why the Scopes Trial attracted so much interest in 1925.

***********************************************************************

3. The Trial

3.1 The Tennessee Evolution Law

By 1925, states across the South had passed laws prohibiting the teaching of evolution in the classroom. Oklahoma, Florida and Mississippi had such laws, and narrow margins determined those in North Carolina and Kentucky. The Tennessee Evolution Statute, also called Butler Law after Tennessee representative John W. Butler who had drafted the bill, was passed by the Tennessee House, 75 to 5, and the Senate by a vote of 24 to 6 on March 13, 1925. The Statute prohibited the teaching of any theory that denied the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man had descended from a lower order of animals. This was valid for any of the Universities, and all public schools of the State which were supported in whole or in part by the State's public school funds. Any teacher found guilty of the violation of the Statute should be fined between one hundred and five hundred $ for each offense (http://www.law.umkc.edu).

3.2 The Antagonists

One major point explaining the enormous public interest in the Scopes Trial was the verbal battle between one of Scopes's attorneys, Clarence Darrow, and William Bryan, who aided the state prosecutor. Their enmity was obvious. Bryan had called the trial a contest between evolution and Christianity, even a duel to death, and his opponent the greatest atheist or agnostic in the US. Darrow, on the other hand, joined the defense because he had wanted to put Bryan in his place as a bigot for years (http://xroads.virginia.edu)

3.2.1 Clarence Seward Darrow (1857-1938)

An American lawyer, Darrow became famous as defender of the 'underdog' and staunch opponent of capital punishment. He exerted his tremendous courtroom skill successfully in behalf of more than 100 persons charged with murder, some of his cases arousing high public interest. As an attorney in the Scopes Trial, he argued that academic freedom was being violated by the Butler Law and claimed that the legislature had indicated a religious preference, violating the separation of church and state. He also maintained that the evolutionary theory was consistent with certain interpretations of the Bible. In an especially dramatic session he sharply questioned Bryan on the latter's literal interpretation of the Scripture. Many felt, though he lost the case, that Darrow's examination of Bryan on the witness stand did much to discredit fundamentalist interpretation of the Bible (http://www.encyclopedia.com).

3.2.2 William Jennings Bryan (1860-1925)

An American lawyer and political leader, Bryan was known as ‘The Great Commoner’ to the people. He was a three-time presidential candidate ('Presidential Hopeful') and former Secretary of State to Woodrow Wilson. Bryant was a leading member of the Democratic party, who identified himself with the free silver forces in Congress. The chief issue of Bryan’s unsuccessful Presidential campaign in 1896 was his proposal for free and unlimited coinage of silver, which he thought would remedy the economic ills then plaguing farmers and industrial workers. In his second run in 1900 the campaign emphasis was on anti-imperialism. He then lost a second time against the Republican McKinley. In 1908, he was defeated by Roosevelt’s candidate William H. Taft. In spite of this repeated rejection by the nation, many of the reforms he urged (income tax, popular election of Senators, woman suffrage, public knowledge of newspaper ownership, prohibition) were eventually adopted. Bryan was the nations most famous spokesman for rural American. After a few years of retirement, Bryan, a Presbyterian, joined the fundamentalist Chautauque circuit to preach against Darwin in tent revivals across the country, and addressed legislatures urging measures against teaching evolution. The climax of his fundamentalist activities was the Scopes Trial. Although he won the case, his beliefs were subjected to public ridicule in an examination by Darrow. Five days after the trial Bryan died from his diabetes (Cayton & Williams, 2001, http://www.encyclopedia.com, http://xroads.virginia.edu)

3.3 Chronology of Events

Soon after the Butler Law was passed, the American Civil Liberties Union in New York (ACLU), which was becoming increasingly more wary of what they saw as an infringement on constitutional rights, set out to initiate a court case to test the constitutionality of the law. They posted a press release in a Tennessee newspaper offering legal support to any teacher who would challenge the law. George W. Rappelyea from Dayton, a small Tennessee mining town, spotted this press release and, together with other local leaders, hammered out a plan to bring the spectacular trial to Dayton, thus serving the evolution cause and promoting their hometown at the same time. In the 24-year old John T. Scopes they found a biology teacher who was willing to challenge the Butler Law (http://xroads.virginia.edu).

The Trial of John Scopes took place at the Dayton courthouse in July 1925. Since the objective was to challenge the contstitutionality of the Anti-Evolution Law, Darrow wanted the jury to find Scopes guilty, so he could then appeal to a higher court. Besides, he had planned to call expert witnesses to give testimony about evolution, but the judge denied this request. In order to block Bryan from delivering his meticulously prepared summarizing speech, Darrow asked for an immediate direct verdict, which was granted. Scopes was found guilty of violating the state law and had to pay the minimum fee of 100$. But despite the verdict, the sensationalism of the trial discredited fundamentalism in intellectual circles, and liberalism seemed triumphant (Cayton & Williams, 2001, http://xroads.virginia.edu).

The Trial itself passed on to the State Supreme Court in Nashville, which handed down a decision that reversed the earlier one in January 1927. However, the decision stemmed from a mere technicality (by Tennessee state law, the jury, not the judge, must set the fine if it is above $50) - the very thing Darrow had sought to avoid. Thus, the constitutionality of the Butler Law stood untested and the question whether the First Amendment permitted states to ban the teaching of a theory that contradicted religious beliefs remained unresolved until 1968 (Epperson vs Arkansas), and again in 1987 (Edwards vs Aguillard), when the Supreme Court ruled that such a ban is not constitutonal (http://xroads.virginia.edu, http://www.law.umkc.edu).

3.4 The Public

Public interest in the Trial, also called the Scopes ‘Monkey’ Trial, was running high, even abroad. During the twelve days in court, Dayton swarmed with politicians and lawyers, preachers and university scholars, reporters and even circus performers. The streets of Dayton took on the appearance of a small-town fair, with people selling food, souvenirs and religious books. On the side of the courthouse ran a banner blaring "Read Your Bible Daily!," while others said "Prepare to meet Thy God" or "Repent or Be Damned." The reporters came from as far away as Hong Kong, and collectively they penned more than two million words during the trial. In this respect, the Scopes trial met all of Rappelyea's expectations and more. Dayton had become the centerpoint of worldwide public interest. Public sentiment was clearly in favor of Bryan and the fundamentalist point of view. The townspeople came to see the trial in record numbers, packing the small country courthouse. Because of the heat and the fear the courthouse might break down under the weight of so many spectators, the trial was moved outside, and there, Darrow called Bryan to the stand to question him on his literal interpretation of the Bible. Darrow emerged victorious from the confrontation, and the public sentiment was brought over to his side (Curtis, 1956, http://xroads.virginia.edu).

3.5 The Press

The press, national and international, was omnipresent at the Scopes Trial. With more than 200 reporters present, there had never been a trial thus thoroughly covered by the mass media. Chief among the media was H.L. Mencken of the Baltimore Sun. He was one of the alienated intellectuals of that time who ridiculed small-town Americans, Protestant Fundamentalism, complacent middle-class life, and the politicians in his magazine, The American Mercury. Mencken was known for his caustic wit and cynical observations and constantly mocked the hopelessly backward and narrow-minded ‘hicks’ (stupid farmers) and the Fundamentalist ‘crusaders,’ who persecuted Scopes, in his dispatches. He made the Scopes trial a battleground between rural tradition and urban modernism. Common misconceptions about the trial arouse from his comments which suggested that a mob-like atmosphere dominated the trial with Scopes and Darrow insulted, jeered or even menaced, whereas other contemporanous accounts present the trial as quite civil with an atmosphere of pleasant festivity. Town leaders obviously wanted to make sure that their town left a favorable impression in the public mind. Newspaper headlines read, for example, "Cranks and Freaks flock to Dayton," "Stormy Scenes in the trial of scopes as darrow moves to bar all prayers," or "Europe is amazed by the scopes case," and lots of funny to scathing caricatures were displayed on the front pages. In addition to the extensive covering by print media, the Scopes Trial was the first ever broadcast on radio (Cayton & Williams, 2001, Easterbrook, n.d, Curtis, 1956, http://xroads.virginia.edu).

3.6 The Biology Book

The textbook Scopes used for teaching biology was Hunter’s A Civic Biology. Its presentation of evolutionary theory was both eugenic and racist, advocating the improvement of future generations of men by applying the laws of selection as in animal breeding, and ranking the races according to how high each had reached on the evolutionary scale. According to the book, there are five races or varieties of man, whereof the Caucasian type, represented by the civilized white inhabitants of Europe and America, is the highest. In spite of the book being at the bottom of the Scopes case, its questionable content was never discussed during the trial and has been widely overlooked in the assessment of the Scopes Trial (Wiker, 2002).

3.7 Hell and the High Schools

A conspicious sight during the Scopes Trial were stands selling religious tractates and books. Besides works by Bryan, one of those stands was selling copies of the popular book "Hell and the High Schools" by Evangelist T. T. Martin (1923), which ardently attacked evolution. It is an excellent example to illustrate the fundamentalist polemic of those days. In his book, Martin called the teaching of Evolution the greatest curse that ever fell upon this earth, and evolutionary theory a deadly, soul-destroying poison. He even stated that it was worse than war or a deathly epidemic, since it condemned the children who are taught this theory to spend eternity in hell. Therefore, he fervently called upon mothers and fathers to exert all their influence on school boards not to employ teachers who believe in evolution, and to make teachers expose the claims of evolution every time it comes up in the textbooks, which often were poisened with the theory. Books like "Hell and the High Schools" fuelled the conflict between Fundamentalists and Darwinists (http://www.law.umkc.edu).

***********************************************************************

4. Scopes today

4.1 How the Scopes Trial is percieved today

To several famous lawyers of today, the Scopes Trial is the greatest trial of the 20th century, because it was about ideas, about whether science and religion could be reconciled, about the limits of academic freedom, about the influence of religion, about who controlled the schools and who determined the laws. It was a symbolic struggle for America’s culture between the forces of traditionalism and modernism bringing together one of America’s greatest defense attorneys, Clarence Darrow, one of its most popular political orators, William J. Bryan, and one of its greatest and most acerbic journalists, H.L. Mencken. Therefore, the Scopes Trial is still frequently talked about today, after more than 75 years, and it even inspired one of the greatest courtroom dramas, "Inherit the Wind," . starring Spencer Tracy as Darrow, Fredric March as Bryan, and Gene Kelly as Mencken (Lindner, 1999, http://xroads.virginia.edu).

4.2 Anti-evolution Activities

The Scopes Trial tended to discourage other states from enacting anti-evolution laws of their own at that time. But, the conflict between science and religion has not ended yet. Anti-evolutionary sentiment has been extensive in popular culture even today, with 47 percent of Americans, including one-fourth of college graduates, believing that God created men and women in their present form at one time within the last ten thousand years (Cayton & Williams, 2001). Only about nine percent of Americans accept the central finding of modern biology that humans and all other species have slowly evolved from a succession of more ancient beings by natural processes without divine intervention needed in the process (McGlynn, 1998). The debate over teaching evolution in public schools is still raging in the 21 century. Religious Right activists continue to push Creationist agendas in many communities around the USA, partly with some success. The Kansas Board of Education, for example, decided in 1999 to remove evolution, as well as the Big Bang theory, and any mention of the age of the Earth, from the state science standards. This only was revised in 2001 after a major outrage from educators, scientists, students and parents. In 2001, anti-evolution bills were introduced in the Michigan and Arkansas state legislatures. Pennsylvania is considering revisions to its state science standards that would include requirements that students be familiar with arguments against evolution. In Alabama and Oklahoma, a disclaimer is required in all textbooks stating that evolution is a controversial theory, not a scientific fact. In Colorado, the State Board of Education has drafted standards that do not require evolution to be covered on state science tests. And President George W. Bush indicated that he believes both evolution and creationism ought to be taught in public schools. There are many more examples for the activities of Fundamentalist religious groups trying to influence the syllabus of public schools, and there does not seem to be an end to it in the near future, either.

***********************************************************************

5. Conclusion

The Scopes ‘Monkey’ Trial of 1925 was one of many events in a long chain of struggles between science and religion. But it is much too simplistic to see it merely as a battle between enlightened and modern urban intellectuals against ignorant religious fundamentalists from backward rural areas. The trial was the expression of a deep conflict within a rapidly changing society, a society at the watershed between traditionalism and modernity. The cultural changes and turmoil of that period made many Americans, especially older people and those in rural areas, who were not able to or did not want to adapt easily to modern life, seek refuge in the Bible as one anchorpoint of stability and security. They were the people who were left behind by the rapid progress in science and technology and the steady urbanization and modernization of society. The increase in Fundamentalism and the growing resentment towards everything that was associated with the city, including the findings of science, thus is explainable as an anti-reaction to rapid social change. The period was characterized by many confrontations between traditionalist forces and modernist forces but most did not attract more than local interest. What made the Scopes Trial so special was, most of all, the deliberately arranged media circus. Though Scopes was convicted and the Trial did not solve the question whether anti-evolution laws were constitutional, it was a severe drawback for Fundamentalism. Today, the Scopes ‘Monkey’ Trial is still seen as one of the most outstanding trials of the 20th century. And, the conflict between science and Fundamentalism is not yet over. There have been attempts by Creationists to ban the teaching of evolution from the syllabus of public schools again and again, or, at least, attempts to make sure that evolution is taught as a controversial theory, not fact, with Creationism as an alternative. The Scopes Trial, therefore, has not lost any of its actuality.

***********************************************************************

Sources

Boyer, Paul (2002). The Enduring Vision. A History of the American People. 5th edition. Lexington, MA: Heath.

Cayton, Mary K., Williams, Peter W. (Eds) (2001). Encyclopedia of American cultural and intellectual history. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Curtis, W.C. (1956). D-Days at Dayton: Fundamentalism vs Evolution at Dayton, Tennessee (23.11.03)

Easterbrook, Gregg (n.d.)(23.11.03)

Linder, Doug (1999, Jan 28th) (23.11.03)

McGlynn, Edward (1998, 14. July) (28.11.03)

Wicander, R. & Monroe, J.S. (1989). Historical Geology. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Company.

Wiker, Benjamin (2002, February 16-17)(28.11.03)

encyclopedia.com (23.11.03):

http://www.encyclopedia.com/html/section/evolutio_HistoryofEvolutionaryTheory.asp

http://www.encyclopedia.com/html/D/DarwinC1R1.asp

http://www.encyclopedia.com/html/section/Bryan-Wi_PresidentialHopeful.asp,

http://www.encyclopedia.com/html/section/Bryan-Wi_LaterYearsandtheScopesTrial.asp,

http://www.encyclopedia.com/html/B/Bryan-W1i.asp,

http://www.encyclopedia.com/html/D/Darrow-C1.asp,

http://www.encyclopedia.com/html/S/Scopestr.asp

law.umkc.edu (23.11.03):

http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/scopes/SCO_BUT.HTM

http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/scopes/tennstat.htm

http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/conlaw/evolution.htm

http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/scopes/hellandhighschool.html

virginia.edu (28.11.03)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~